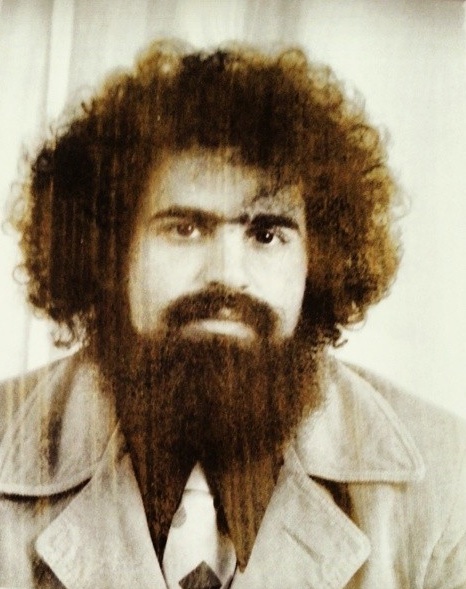

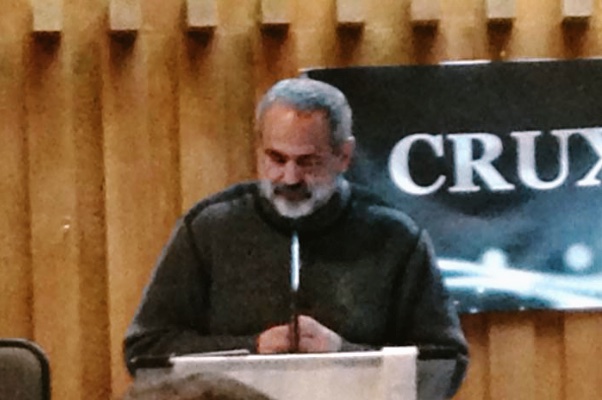

4 Questions: Foster Freed

This article is part of our series 50 Years of Disruption, in celebration of the Department of Theatre’s 50th Anniversary. In it, we’ll ask each participant four questions about themselves and their time at York.

1. Who are you?

Foster Freed (BA Honours, Theatre Studies, 1976) I’ll begin by acknowledging a nagging foreboding: that not every reader of this profile will find themselves agreeing that I am an entirely appropriate candidate for inclusion in a group of alleged “disruptors”. For that matter, I am not myself entirely convinced that I belong in such a group, although there is no denying that I have been quite adept, over the years, at “disrupting” other folks’ expectations of the path my life would likely take. Those who knew me when I entered McGill as a Maths/Physics major in 1968, would not likely have imagined—when I finally managed to earn a bachelor’s degree eight years later—that it would be from a University Theatre Department. In much the same way it is safe to speculate—had my York Theatre graduating class been polled at the time, and had that poll queried as to which of their fellow graduates was least likely to end up spending the bulk of their professional life as a Minister with the United Church of Canada—surely the name of this “Bertholt Brecht-worshipping” radical would have appeared at or near the top of most such lists, including my own. Nevertheless: there you have it! Having entered into a period of spiritual restlessness during my final couple of years at York, this “comfortably secular Jew” unexpectedly found himself on a trajectory that “uncomfortably” led to his baptism late in 1980, his admission to the United Church of Canada the following year, entry to the M.Div. programme at Vancouver School of Theology in 1986, followed by graduation and Ordination in the Spring of 1990. After a three-year stint with a congregation in Northern Ontario (Hornepayne), I have served out the rest of my ministry on Vancouver Island. Whether any of that qualifies as disruptive likely depends upon one’s willingness to credit the impact and implications of the marginalization the Church-in-Canada has experienced in my lifetime, a Canada in which scarcely ten-percent of the population is likely to attend Christian worship on any given Sunday. What cannot be denied, however, is the extent to which my four years at York continues to shape the work I do—in ways expected and in ways surprising—as a preacher, as a designer-of and presider-at weekly worship, as a small-group facilitator and as a pastoral-care provider. More on that below!

2. What was your favourite moment during your time in the Theatre Department, and why?

I am going to share two such “moments”.

I arrived at York as a second-year Theatre Studies student in the Fall of 1973. The following Fall, John Juliani arrived on campus—under the auspices of the Theatre Department—to launch a two-year master’s degree Programme with a primary emphasis on performance. In the Fall of 1975, John and his company were invited to participate in a fringe-theatre festival being held in the Polish city of Wroclaw, home to Jerzy Grotowski’s renowned “Teatr Laboratorium”. John’s funding permitted him to bring along one additional student; on Don Rubin’s recommendation, I was invited to be that student, tagging along as a sort of “critic/dramaturge-on-the-fly”. It was a remarkable and at times turbulent month, involving not only time-spent at the festival itself—where we gained exposure to a remarkable array of experimental theatre companies from around the world—but also a subsequent “tour” of Poland, offering performances at a handful of stops along the way. Given the highly improvisational nature of the work offered by John’s company, there were even times during that hectic month when the line between my role as “critic-observer” and an unexpected role as “fringe performer” grew increasingly thin. All-in-all, an unforgettable experience.

The second “moment” involves the fact that—upon my graduation in 1976—I remained on the York campus for an extra 12 months. Why? For the previous two years, I had been a fixture inside the office of the Canadian Theatre Review, one of a handful of students who worked with Don Rubin, founding editor of the Review. Beginning in the Fall of ’76, Don spent a 12-month sabbatical in Europe; given that this was long before the advent of the internet, he needed someone to serve as CTR’s Managing Editor, and I was the fortunate designate! Of the four issues I helped to “birth”, I am especially “proud” of an issue devoted to the theme of “Homosexuality and the Theatre”, an issue in which Eric Bentley served as Guest Editor. Recall that in 1976 and 1977, bathhouse raids were still a common occurrence in Toronto; indeed, the notorious “Operation Soap” would not take place for another five years! The experience of working on that particular issue of the Review—including hosting a panel discussion that was published as part of the issue—was both challenging and rewarding. Given the way in which questions surrounding human sexuality have impacted the United Church of Canada over the past 40 years, working on that issue turned out to be a remarkably important and formative experience.

3. What comment, quotation, statement, or action that a professor—or classmate—offered had the greatest impact on you?

I imperfectly recall—no doubt he’ll correct me if I get it entirely wrong—an anecdote Don Rubin shared with our Theatre Criticism class. Speaking of those occasions when he was approached in a theatre lobby—on the way out after a production and asked what he thought of the production—he would sometimes reply: “I won’t know until I write my review.” That has actually been exceptionally helpful to me as someone who writes something in the order of 45 sermons a year which (at roughly four pages per sermon) works out to between five and six thousand pages over the course of a 30-year ministry career. Experience has taught me the truth of Don’s quip and, in the process, taught me to respect the process of writing: not merely as a way of expressing one’s thoughts, but as a revelatory process in which one’s thoughts can best be permitted to crystallize.

4. Is there a way you incorporate a particular aspect of your theatre training in your current work?

That’s the really funny and ironic question, because the surprising answer is that it has been helpful in every conceivable way. When I first entered seminary in 1986, there was a tiny part of me that regretted not having attained my undergraduate degree in a more “relevant” field: philosophy, theology or even political science. Within the first month, however, it became clear that my undergraduate degree in theatre was more useful than any other course I conceivably could have taken. The exegetical work I do week-by-week as I ponder a scripture passage, has close parallels to the exegetical work actors, directors, designers and theatre critics need to do in order to engage a script. The small groups I facilitate—both study groups and support groups—draw heavily upon the experiences with human interaction that was part of my training as someone with a key interest in directing. And since weekly worship involves at least some degree of “public performance”, I know that my time at the York Theatre Department has been beneficial in that regard, as well. Whenever a young person, including two of my own four, expresses an interest in studying theatre, I am always confident—regardless of the career path they will eventually follow—that their studies will prove to be of great and abiding benefit. That certainly proved itself true for me.